I’ve noticed something about books on India’s freedom movement. The big timeline histories can be impressive, but the stories that stick to my ribs are the ones that feel close enough to touch. A jail cell that smells of sweat and damp paper. A hunger strike that turns days into an endless thread. A young activist learning, the hard way, what the British state could do when it felt cornered. Memoirs put you right there, and they make the past feel less like “history” and more like somebody’s life that got spent for an idea.

What I love most is how messy, human, and unfinished these accounts can feel. The freedom struggle wasn’t a single mood or a single strategy. It had students and workers, idealists and pragmatists, people who carried pamphlets and people who carried weapons, people who fought inside India and people who fought from far away. Memoirs and memoir-based narratives show those contradictions without trying to smooth them out for you. They let you sit with the hard parts, like doubts, mistakes, betrayals, and the weird emptiness that can follow a victory.

And here’s the part I didn’t fully expect the first time I went down this rabbit hole. A lot of these stories are not only about beating colonial rule. They’re about what that fight did to the fighters themselves. You see how a person’s politics forms under pressure, how prison can turn someone into a reader and a thinker, how exile can sharpen a sense of identity, and how independence can still leave people feeling ignored, tired, or sidelined. If you’ve ever wondered what the revolution felt like on the inside, these are the kinds of books that answer it.

What are the top Books on India’s Freedom Struggle?

In The Shadow of Freedom, by Kaushik Raha (2025)

This one reads like a family passing a torch from hand to hand. It’s adapted from the recovered memoir of Lalit Chandra Raha, a Bengali freedom fighter, and it carries that intimate I was there energy that you can’t fake. You’re not watching the revolutionary movement from a balcony. You’re walking through it with someone who is trying to make decisions in real time, with real consequences.

The story’s center of gravity is pre-independence Bengal and the Jugantor dal, where activism wasn’t a slogan, it was a daily risk. It moves through the Khilafat and Swadeshi currents, and it doesn’t treat them like neat textbook chapters. You can feel how movements overlap, how alliances form and fray, how the idea of the cause becomes a practical question of money, secrecy, and stamina. The robbery to fund revolutionary work, and the atmosphere around plots like the attempted assassination of Commissioner Castle, bring out that tense, half-underground vibe that defined so much of the era.

Then the book shifts into the prison world, and it gets even heavier. The Cellular Jail in Port Blair isn’t just a location, it’s a pressure cooker. The hunger strike, the deprivations, the daily grind of surviving a system designed to break people, it’s all there. What surprised me is how the memoir tracks an intellectual transformation inside that hardship, with reading and study becoming its own form of resistance.

What I liked most is the three-generations framing, because it quietly admits something important. Memory is fragile, and every retelling has choices baked into it. Instead of pretending that’s not true, the book leans into it, and that makes the emotional punch land harder. The strength here is how it shows both the fire of the struggle and the complicated aftermath, including the disillusionment some fighters felt in post-Partition India.

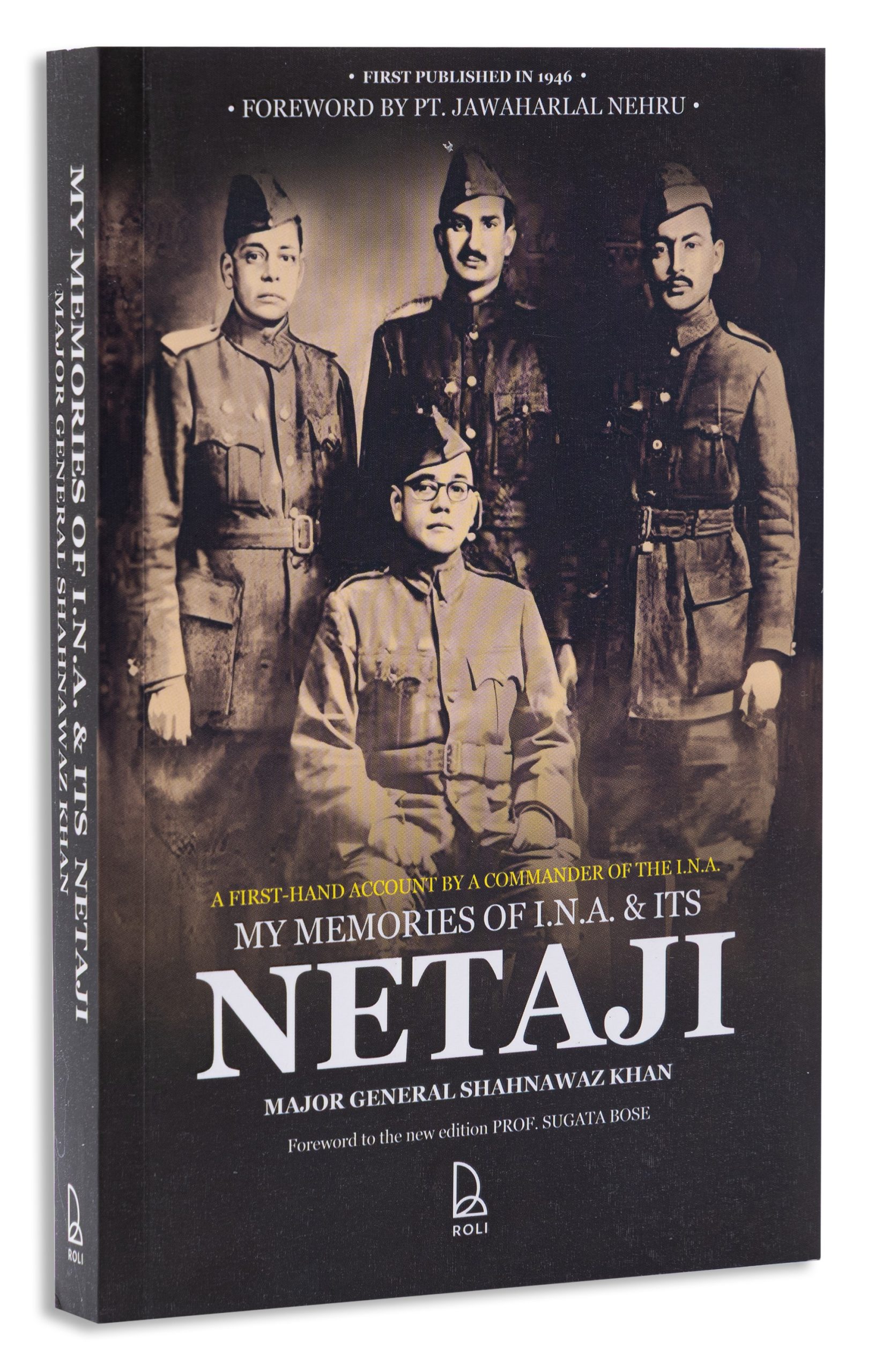

My Memories of I.N.A & Its Netaji, by Shahnawaz Khan (Maj. Gen.) (2024)

If you want a memoir that feels like it was written by someone who stood close to the engine of history while it was running, this is it. Shahnawaz Khan was not a distant commentator. He was a commander inside the Indian National Army orbit, and his account is shaped by proximity, loyalty, and the kind of lived detail that doesn’t come from research notes.

The memoir pulls you into the INA world in a way that’s both political and personal. You see how the Second World War cracked open unexpected pathways for anti-colonial action. You also see how charisma works in revolutionary movements, because Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose isn’t just a name in this book. He’s a presence. The narrative makes you understand why men would take extreme risks for him, even when the odds looked brutal.

One thread that keeps tightening is the question of legitimacy. The INA story has always sparked arguments about strategy, ethics, and outcomes. A first-hand account doesn’t magically settle those arguments, but it does something better. It shows you what it felt like from the inside, when choices had to be made fast, when propaganda, morale, and survival all mattered at once, and when the idea of “treason” depended entirely on who was writing the law.

I liked this book because it doesn’t pretend to be neutral, and that’s exactly why it’s valuable. You’re reading a committed perspective, and you can feel the author trying to honor what he sees as courage, sacrifice, and a kind of disciplined audacity. The strength is how it makes the INA feel real, not mythic, with all the weight that comes with that.

Jail Diary and Other Writings, by Bhagat Singh (2024)

Bhagat Singh has a strange fate in public memory. People chant his name, print his face on posters, and sometimes flatten him into a single heroic pose. Jail writing does the opposite. It gives you a person thinking, arguing, reading, sharpening his beliefs, and staring down the state from a cell. This collection is powerful precisely because it refuses to keep him at a safe distance.

The prison context matters. Jail isn’t only punishment here, it’s a setting where ideas get tested. The writing carries the pressure of time running out, and you can feel the author working to make meaning out of confinement. The topics move through politics, ethics, the logic of resistance, and the personal discipline required to keep going when the system wants you exhausted and afraid.

What also hits hard is the voice. Even when you don’t agree with every conclusion, you can respect the clarity and the seriousness. It’s not “inspirational quotes” material. It’s a window into a young revolutionary mind trying to build a coherent worldview, with colonial power sitting on the other side of the wall.

I liked it because it’s the antidote to shallow hero-worship. The strength is that it makes you meet Bhagat Singh as a thinker, not a symbol. And honestly, once you’ve read him in his own words, it’s hard to go back to the simplified version.

An Indian Freedom Fighter in Japan, by A. M. Nair (2025)

Most people picture India’s freedom movement as something that happened on Indian soil, under British eyes. This memoir flips the map. A. M. Nair’s life shows how anti-colonial politics also moved through cities like Kyoto and Tokyo, through wartime Asia, and through networks that were part diplomacy, part activism, part sheer survival.

The account shines when it gets into the Indian Independence League and the INA’s international dimension, including leadership figures like Rash Behari Bose and Subhas Chandra Bose. Instead of repeating familiar narratives, it adds friction and texture. You see how ideology and logistics collide when you’re operating abroad. You also see how messy alliances can get when global war is the background noise and everyone is trying to use everyone else.

Nair’s memoir also feels like a biography of reinvention. Student, organizer, adviser, entrepreneur. That shape matters, because it suggests something about what revolutionaries had to become, not just what they had to do. Independence work wasn’t a single role you clocked into. It could swallow your entire identity and then force you to rebuild it again later.

I liked it because it widens the story without diluting it. The strength is the perspective shift. It makes the freedom struggle feel like a global chessboard where individual lives were still on the line, and where the cost of commitment followed people even across borders.

The India I Saw: An Autobiography, by S. Ambujammal (2025)

This is the kind of memoir that sneaks up on you. It’s not built around a single dramatic act, like a bombing or a jailbreak, but it can be just as intense because it shows how freedom struggles live inside daily life. Ambujammal’s autobiography carries you through a long stretch of twentieth-century Madras, with the national movement beating in the background like a drum you never stop hearing.

What makes it gripping is the angle. You’re not only reading politics, you’re reading social reality. Family expectations, gendered limits, the slow burn of reform, and the way “public causes” and “private pain” overlap until you can’t separate them. If your mental image of the struggle is mostly male leaders and big rallies, this book adds the missing rooms of the house.

The narrative also has a quiet kind of courage. It doesn’t need to shout “revolution” to show you what it costs to live through upheaval, carry responsibilities, and still try to orient your life toward something larger than yourself. There’s an honesty here about hardship that feels earned rather than performative.

I liked it because it gives the freedom movement a lived environment. The strength is the human scale. You come away feeling like independence wasn’t only forged in speeches and prisons, but in homes, streets, friendships, and stubborn choices that didn’t look heroic in the moment.

An Indian Pilgrim: An Unfinished Autobiography, by Subhas Chandra Bose (2025)

There are revolutionaries who become legends, and there are legends who still feel like strangers. Bose’s unfinished autobiography is one of the better ways to close that distance. Instead of meeting him through other people’s arguments about him, you meet him through his own attempt to narrate his formation, including the inner life that fed the outer politics.

The early-life focus is important. A lot of accounts start when a figure is already “important.” This kind of autobiography shows the slow build, education, spiritual searching, and the uneasy relationship between personal ambition and a moral calling. It also makes the freedom struggle feel less like a stage Bose stepped onto and more like a direction he kept moving toward, even when it complicated everything else.

Because it’s unfinished, the book has an oddly modern feel. It doesn’t wrap up neatly, and it doesn’t try to turn the author into a perfectly consistent character. You’re left with momentum, questions, and a sense of someone writing under the weight of history while still being a person with contradictions.

I liked it because it adds depth to a figure who is too often treated like a political Rorschach test. The strength is how it lets you see Bose before the icon hardens, while the choices are still forming, and while “revolutionary” is not a label but a path he’s walking into.

Final thoughts

If you read all six, you end up with something like a 3D picture of the freedom struggle. Not a single narrative, not a clean moral fable, but a set of lives that intersect with a huge historical force. Some of these writers look outward at the machinery of empire, and some look inward at what the fight did to their beliefs. That mix is the point. Revolution isn’t only a political event. It’s a psychological one.

I also think memoirs do a specific kind of justice. They make it harder to treat sacrifice as abstract. A five-year sentence, a hunger strike, exile, disillusionment after independence, those stop being phrases and start being lived time. When people ask why these stories still matter, that’s the answer I keep coming back to. Memoir forces you to feel the human cost, and it makes cheap cynicism harder to hold onto.

And if you’re picking where to start, I’d match the book to the kind of intensity you want. If you want prison-hard and mind-sharp, go for Bhagat Singh’s writings. If you want underground Bengal and the brutal geography of punishment, start with Lalit Chandra Raha’s story as shaped by his family. If you want the wider chessboard, take the Japan memoir. However you choose, you’ll end up with a more honest sense of what “freedom” demanded from the people who chased it.

My profession is online marketing and development (10+ years experience), check my latest mobile app called Upcoming or my Chrome extensions for ChatGPT. But my real passion is reading books both fiction and non-fiction. I have several favorite authors like James Redfield or Daniel Keyes. If I read a book I always want to find the best part of it, every book has its unique value.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·